A play on tactics, time, timing, and tempo

Sand punctiliously trickles down the hourglass, as the moving part of time advances. It is the symmetry of the structure that entices its sand to seep through at a steadfast rate. Yet, within its rigid shape, the behaviour of the sand is limited to fixed possibilities.

The hourglass, its contribution to time and timing, and its symmetry mirror Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton & Hove Albion side.

Much like the 8th-century invention, the hourglass of De Zerbi and its symmetry forge a scaffolding for its timing and tempo. And much like the restricted movement of the sand, the behavioural patterns within the footballing hourglass are finite, only to the possibilities within.

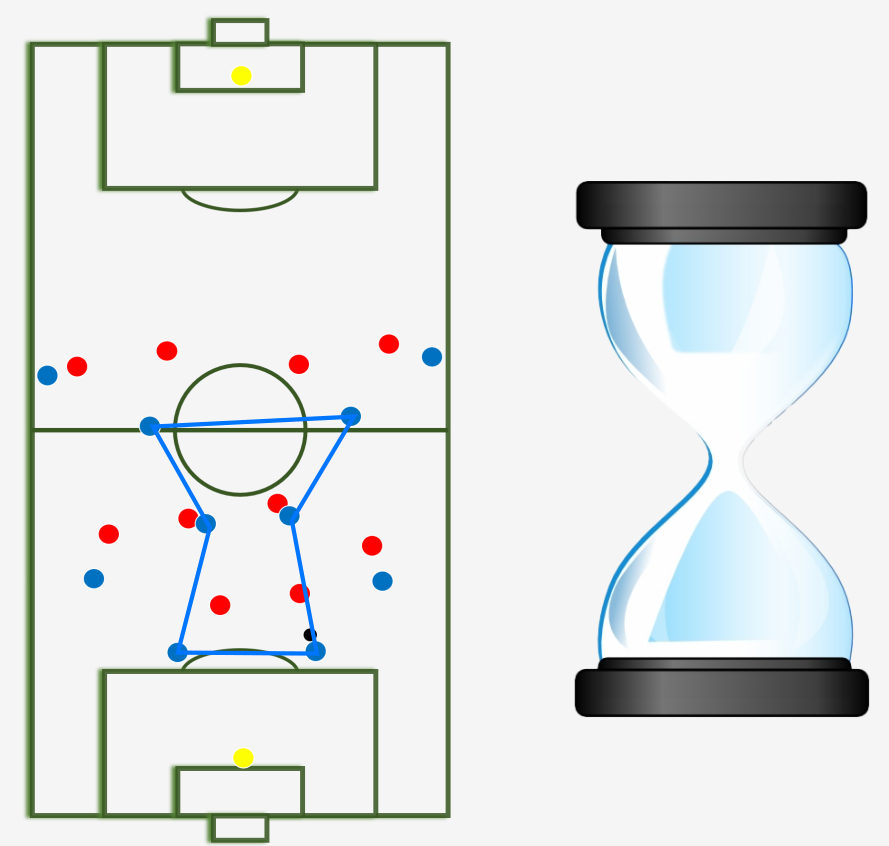

As abovementioned, the symmetric mirroring of Brighton’s build-up structure is a founding stone of the technical and tactical behaviours within the first and second phases of their attacks. The hourglass I refer to is one shaped by two centre-backs, two central midfielders, and two strikers. It is important to remember that this structure is not Brighton’s only form, and that structure is not an end goal, but rather just a product of tactical behaviour.

I “quote” this structure because of its symbolic analogy with timing and tempo.

I. The simplicity of the hourglass (macro)

At the macro level, the hourglass structure facilitates and enables the technical and tactical concepts of Roberto De Zerbi’s game model. It simplifies the control of time and it “plays” with space in a manner measured to the tactical roles of the players. On a group-tactical scale, the hourglass prearranges commending angles for progressive play through and beyond the first two lines of the opposition press.

In many ways, training and playing the hourglass is simple through a few of its characteristics. Nonetheless, the behaviour within is specific, complex, and interesting. Let’s dissect it all.

I.1 Symmetry and simplicity (macro)

The simplicity of the hourglass is formed through its ease of relative positioning or structuring. That means as much as saying the players position themselves relative to their teammates (remarkably, not relative to the opposition). The “neck” of the hourglass, or in Albion terms, Moisés Caicedo (#25) and Pascal Groß (#13), can recognize the horizontal width of their centre-backs and adjust accordingly. For the strikers, the boat floats similarly. Playing angles are therefore easier to create for players who dictate their movements (in this system, especially the strikers).

The angles created are diagonal passing angles, which are naturally more dynamically advantageous for the attacking team. On either side, the full-backs often support the hourglass and create a diamond.

Creating playing angles is a basic possessional principle, supported by the landscape of the very sub-structures Brighton & Hove Albion creates. But its simplicity is deceivingly dangerous – football is a dynamic game, and diagonal passes are difficult to defend against.

II. Training the hourglass’ behaviour

In order to arrive at this structure though, the tactical, technical, and behavioural patterns within it must be taught to the players. That is an important distinction – coaches train the behaviour (in the case of structure, this is “arrive”, “leave” et cetera), not the structure. The structure is only a consequence of said behavioural patterns.

In similar (and not-so-similar ilk*) to his coaching compatriots of Maurizio Sarri and Antonio Conte, Roberto De Zerbi’s offensive play is built upon circuits of play. Antonio Conte, now formerly of Spurs, Chelsea, Juventus, and Inter, governs by an “authoritarian” coaching style. It drains its players’ autonomy when building attacks in the first two phases, through more hard-line circuits to progress the ball, and on Saturday, there are ninety minutes of intense touchline-coaching to guide his players as if he is pressing Xbox buttons.

Roberto De Zerbi too advocates for the use “unopposed” practice in his coaching curriculum (not to say it’s the main part). It designs exercises with no opposition, for example, a 11v0 exercise with the ball starting from the goalkeeper (start and reset point) aiming to end in the opposing net. The opposition would be mannequins, representing the shape of the upcoming opponent.

Observant readers will remark that circuit-based sessions do not simulate game realism. That is, however, not its aim either. Unopposed practice inherently and directly (there is no sub-outcome as in other designs) coaches the circuits at hand. They almost ‘drain’ the brain and its autonomy in decision-making. Their upside, however, is that they control time in a competitive way – by reducing “perception time” (What will I do when I get the ball? What are my teammates doing off the ball?) and minimizing “execution time” (shortening it through the repeated exercise of the same pass), the team’s offensive play paces through the thirds much faster than the defending team can cope.

In the introduction, I declared the “behavioural patterns within the footballing hourglass” to be finite, limited to the possibilities within, like the sand’s behaviour in the age-old hourglass.

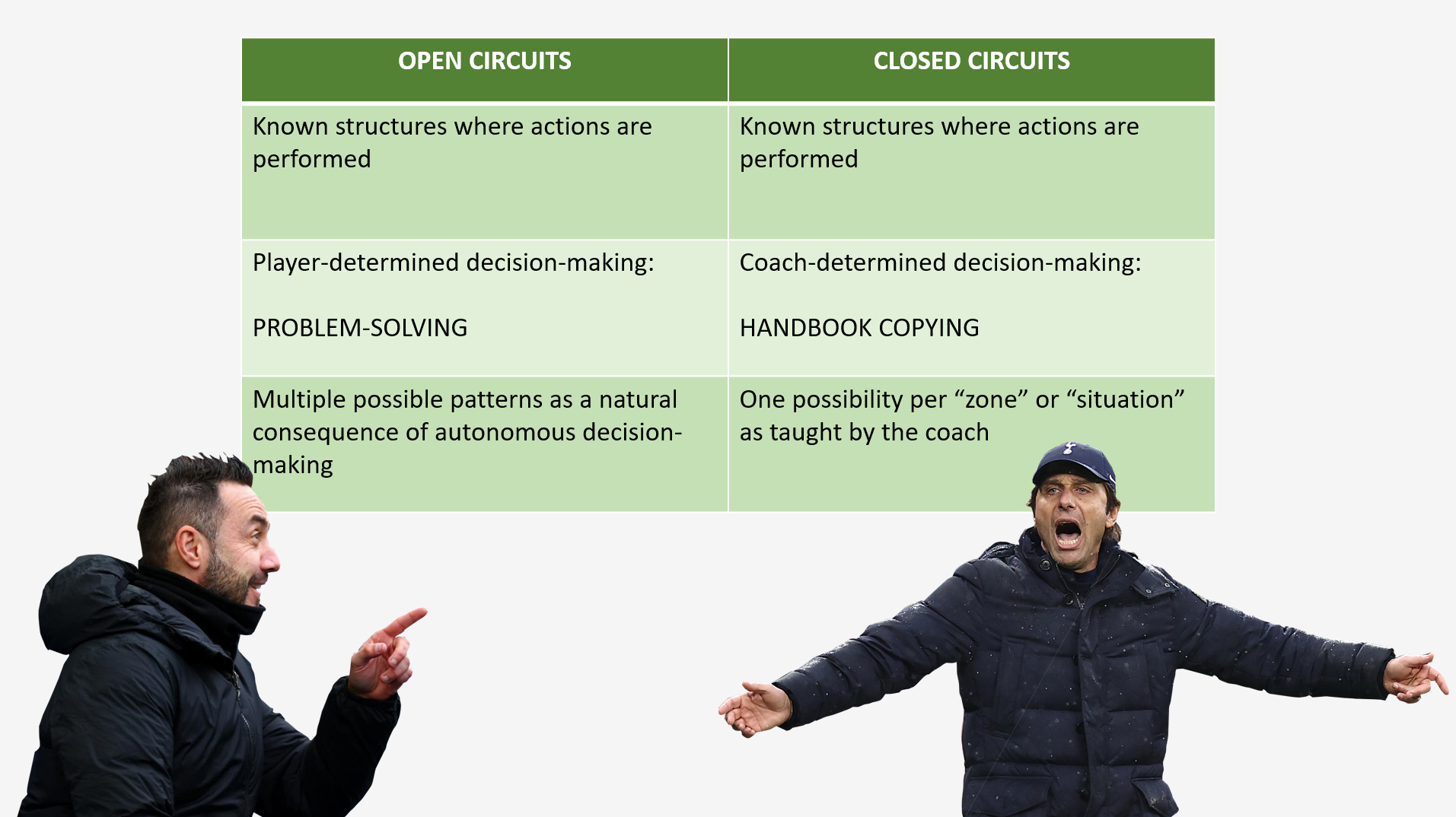

This is where De Zerbi draws the line. The Italian divides unopposed practice into two sections I can best (arbitrarily) describe as open-ended and closed.

“Closed” unopposed exercises converge into a single, pre-determined “solution” or “endpoint”. This exactly is the craft of Conte. The patterns are recognizable in the games – there are patterns for goal kicks, or when the RWB is in possession et cetera. Closed circuits are, essentially, a top-down process.

Closed circuits directly coach all technical, cognitive, and tactical layers of the attack. The “brain-drain” inherent to closed circuits consists of minimizing possibilities:

- set pattern of play

- pre-determined target, minimizing autonomous decision-making

- highly repetitive body orientations and passing techniques per play within the pattern

- top-down process

Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton partially resorts to circuits of play too, yet materializes from a different philosophy than the dominant school of thinking. De Zerbi’s circuits are open-ended, meaning no endpoint is determined and many possibilities exist in the model – starting from the base point. The “base point”, in Brighton’s case usually the centre-backs at the base of the hourglass, serves as a starting and reset point for their circuits.

Open-ended circuits build a stage for the players to consistently build similar attacks. Unlike closed circuits, the direction and ball trajectory are not pre-determined or fixed, and the positioning and techno-tactical behaviour is rather instructed or advised, but not dictated.

In contrast to closed circuits, where the “solution” is given, here it is the players’ responsibility to decipher which pattern is to be used situationally, or as Roberto would say; here the players “find the solution”. Important to note in this philosophy on player autonomy within coaching methodology: De Zerbi mentions the analysis and training process during the week, informing the possible solutions in the next weekend. It is not a fully autonomous decision-making process.

Therefore, the name of open-ended circuits is self-explanatory. Open circuits provide a platform to structure and build attacks, but they do not “control” the decision-making process of players in attack from the first to the final phase. It is a platform upon which players can problem-solve.

On the training ground, the didactic method to coach open-ended circuits of play is, by no surprise, different to close circuits and many other currents of methodology thinking. Here is an example of Roberto De Zerbi coaching at Sassuolo (source: Albin Sheqiri).

The exercise here is made up of a K+5v1 on two thirds of the pitch (first two phases of the attack). Supporting the session are Roberto De Zerbi (halfway line) and his coaches.

The team building the attack (yellow) must progress the ball through the first two thirds, and find a pass through the mannequins at the end. Despite the one opposition player, solely acting as a reference point for the opposing line of engagement, the exercise is unopposed.

Unlike closed circuits, there is no pre-determined “path” for the ball to follow or the players to move (like the Playstation), there are only the movements instructed or advised by the coaches within the structure.

A bland design at first glance, but the profit margins of these exercises show especially in the specifics of building an attack under De Zerbi. Notice Roberto actively coaching the technical and tactical skills within this shape: the individual tactics of staggering the line as the off-ball centre-back, fluctuating the width as the ball-side full-back, the relative body orientation as a midfielder et cetera.

The exercise allows De Zerbi, for whom the tactics within the hourglass are essential to his sides’ build-up play, to coach his players constantly within a repetitive structure. Therefore, the example is a great way to illustrate open-ended circuits. The ball is not ought to follow a path or reach an endpoint, but has merely been passed through one of the patterns available and is now in a position from which the players can “solve” the “problem” and attack the last line of the defence.

The problem-solving as a central pathway to learning is not only reflected in the situation-training (simulating situations on the pitch). In activation modules, warm-up drills or even low-intensity training days (usually one or two days after matchday), De Zerbi’s training methodology aims to provide autonomous decision-making for the players.

While empowering the players through bottom-up authority contains obvious benefits, some of its virtues are hidden underneath that layer. Through opening decision-making in warm-up drills, the players do not rely on repetition to “learn” techniques – but rather they learn to mentally and technically adapt to a new situation in every combination play.

This didactic style teaches players autonomy, and self-sufficiency but more importantly to their technical development, it nurtures them in a differential way. That is the difference between random practice and blocked practice. The former, utilised by De Zerbi, is a method that improves variability and retention of skills, while blocked practice, meaning a repeated practice of one skill under the same conditions, allows less variability, but more learning “gains”.

Finally, there is another methodological approach that characterises De Zerbi’s unique game model.

Training a complex sport such as football – one that requires the endurance of 10km runs on matchday, but also 1-4-20 metres sprints – is a difficult task. Therefore, sports science has developed clearer training periodization, which splits training into speed, agility, power, strength and endurance. In relation to many factors (but mainly recovery and day of the week), the focus shifts each day of the training week.

For some days, it would mean the intensity of training is lowered – imagine matchday +1 or +2.

Roberto De Zerbi uses these physically less-loaded days to still work on game-model-specific details. Below is an example of a small-sided game (SSG). As very smartly pointed out by thewittyjack on Twitter, this is very different from the casual school of training methodology.

SSGs grew in popularity because the small-sided nature – that being an overload of players per square metre of the playing field – stimulated agility and speed, quick decision-making and intensity.

In many of De Zerbi’s small-sided games, the opposite is encouraged – the SSGs are played at a lower tempo – fitting for Brighton’s game model, but also fitting for the learning experience of the players. At a lower pace, the technical and tactical details – think of relative orientation, the combination play, the timing of arrival et cetera, are all retained better in the mind.

III. Specificity within simplicity (micro within the macro)

Within this supposed simplicity, lies the specificity of Brighton’s attacks. This is the micro level of the hourglass.

To accomplish the main principles of their build-up, say “attract pressure deep to create space beyond”, there are many – obvious and not-so-obvious – tactics involved. For organizational purposes, these are divided into individual tactics and team-tactics. While both are separate entities, they must coexist. There is no team-tactic without individual tactics.

While De Zerbi’s training methodology is varied – from open circuits to game-real situations and low-intensity small-sided-games – the open circuits are the main “quarry” for correctional coaching: it allows the coaching staff to interrupt play, and improve on technical and tactical behaviour.

Those habits, the techno-tactical elements (as namedropped by Ahmed Moallin, a huge source of inspiration for this blog), are the founding fundamentals for Brighton’s manipulation of the opponent, of space, and of time. To fully understand the analogy of the hourglass, we must also understand these foundation stones.

III.1 Relative body orientation

A vital cornerstone of possessional play, the body orientation of a player determines the possibilities of “next actions”, the pressure they invite, the time they have on their second touch, et cetera. It is vital in any phase, team, or position.

As we’ll delve into later, De Zerbi’s teams are time-benders, reinforcing the need for relative orientation, accurate and quick reading of the game/situation, and technical play (one-two-three touches) in midfield.

The bodily orientations ought to be relative – meaning they adapt to the relative situation. In the hourglass and its circuits of play, the relative orientation readjusts more than in other build-up patterns.

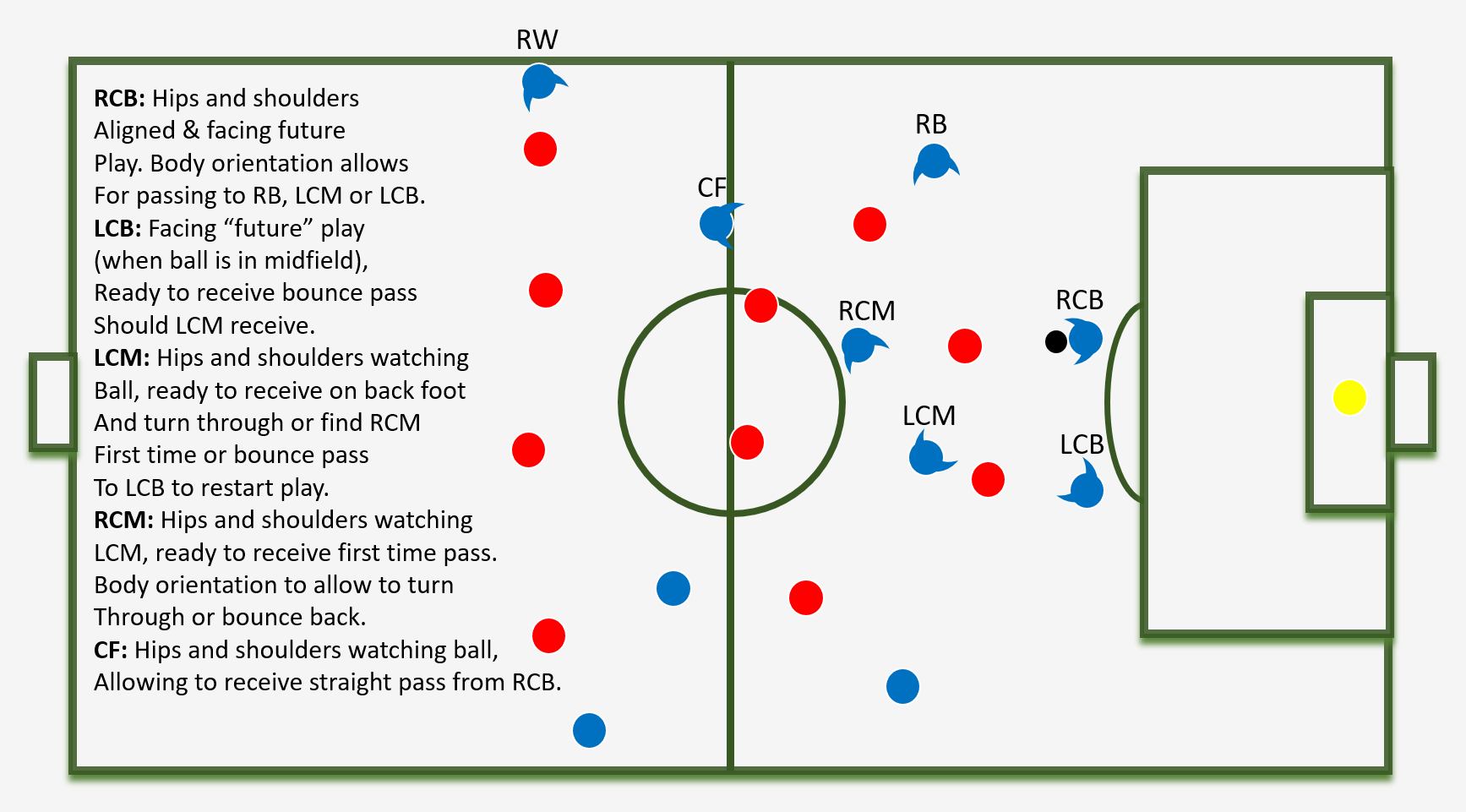

For each player or “pawn” in the play, their body orientation repeats itself many times during a game. The main principle for relative orientation is to use it as part of your next action. For the midfielders, as they have limited possibilities within the hourglass (think of the sand), there are a few orientations they know by heart.

The receiving midfielder, always receiving diagonally from the centre-back, should open his hips to receive on either foot:

Near foot (right foot for Caicedo below) asks the midfielder to play a first-time pass into his midfield partner. On the far foot, Caicedo is allowed to turn through also. If the first receiving midfielder were to receive on his far foot and then release the ball with the other foot (common practice for coaching on all levels), it would slow the timing of Brighton’s attack. Through first-timing the pass from midfielder to midfielder, Brighton’s tempo of attack is much more dangerous. But more on that in chapter four.

The second midfielder ( Groß #13), behind the cover shadow of the forward pressing the centre-back on the ball, has his shoulders facing both goals: his orientation is “side-on”. It is important to play the pass on their far foot, allowing them to get the ball forward on their first touch without breaking momentum. The other option is to bounce the ball back to the first midfielder should they position their body in a way that tells the receiver they’re ready for a bounce.

Groß’s body orientation allows those multiple options. Caicedo’s body language, however, suggests a bounce pass might be the best option for their attack. Notice Moises’ relative orientation *quickly* adapting to the situation, crucial to the effectiveness of Brighton’s build-up.

Forming the corners of the hourglass is centre-forward Danny Welbeck, arriving in the half-space to receive into feet. His body orientation faces his own goal, which invites a “jump” from the centre-back behind him. De Zerbi reasons, however, that despite the seemingly negative orientation from Welbeck, the timing of this movement actually makes the situation a dangerous one for Brighton. When the arrival is timed correctly (right before the pass into your feet can be played), Welbeck has two options. One is safe; the bounce pass to his right-back Veltman (#34). The other, riskier, albeit enabled due to the timing of arrival, is to turn and attack the backline in a 4v4 situation. The advantage lies with Brighton though, as the backline is disorganised following the centre-back’s jump on the dropping striker.

As body orientation not only determines the range of possibilities on the “next action”, but also the tempo of a team’s attack, it is a crucial pillar of Brighton’s possessional play.

III.2 Weighing the ball

Together with relative orientation, the weight of pass contributes to a grander concept by which Brighton builds their attacks.

As previously covered, Brighton’s precise passing to either the near or far foot is a key element of their build-up. Commutual to that principle is the weight of pass.

The direction (either foot), the relative orientation, and the weight of pass are the core factors of “the next action”.

The speed (a consequence of weight) of the ball is what determines the range of possibilities for the ball receiver. Balls with enough speed can be used to “roll” the defender and turn, while those with lesser speed can be bounced in return or create a first-time pass.

Those technical skills are on display in the video shared above. In the first clip, Dunk’s ball to the diagonally-positioned Mac Allister has just enough pace to

- grant him time to calculate ball speed

- therefore allowing him to make an easy first-time pass

- enough time to still be separate from pressing markers

Its speed is not excessive in that it could cramp a first-time pass. It is a pass, exercised countless times. The second pass has a little more speed (MacAllister ADDS speed to the ball), which allows Caicedo to turn and open the pitch.

In the second clip, the first pass from centre-back to midfielder is delivered with similar weight. It allows an easier first-time pass to bait and evade the second (the first press is on the centre-back) press. Groß’s bounce pass tells Caicedo exactly what he needs to know: the German’s pass takes speed OUT of the ball, making it a perfect bounce pass. It is aimed at Caicedo’s strong foot, allowing him to get it out of the zone and through to the last line. Groß knew this was on due to his scan before Caicedo received the ball – where he picked up the opposition midfielder jumping to press.

III.3 Keys to communication, perception, and interpretation

Those details – the weight of pass, direction, and body orientation – all adhere to a larger concept called communication.

While verbal communication is one of football’s biggest themes (and taught earlier in a footballer’s career), the non-verbal communication at Brighton & Hove Albion is the only part this article delves into, as it is more symbolic and unique to their game model.

In the previous sub-chapters, there were some hidden elements to the direction, body orientation and pass weight as fundamentals of communication. These are no inseparable components, as they all serve a communicative function in Brighton’s possession play.

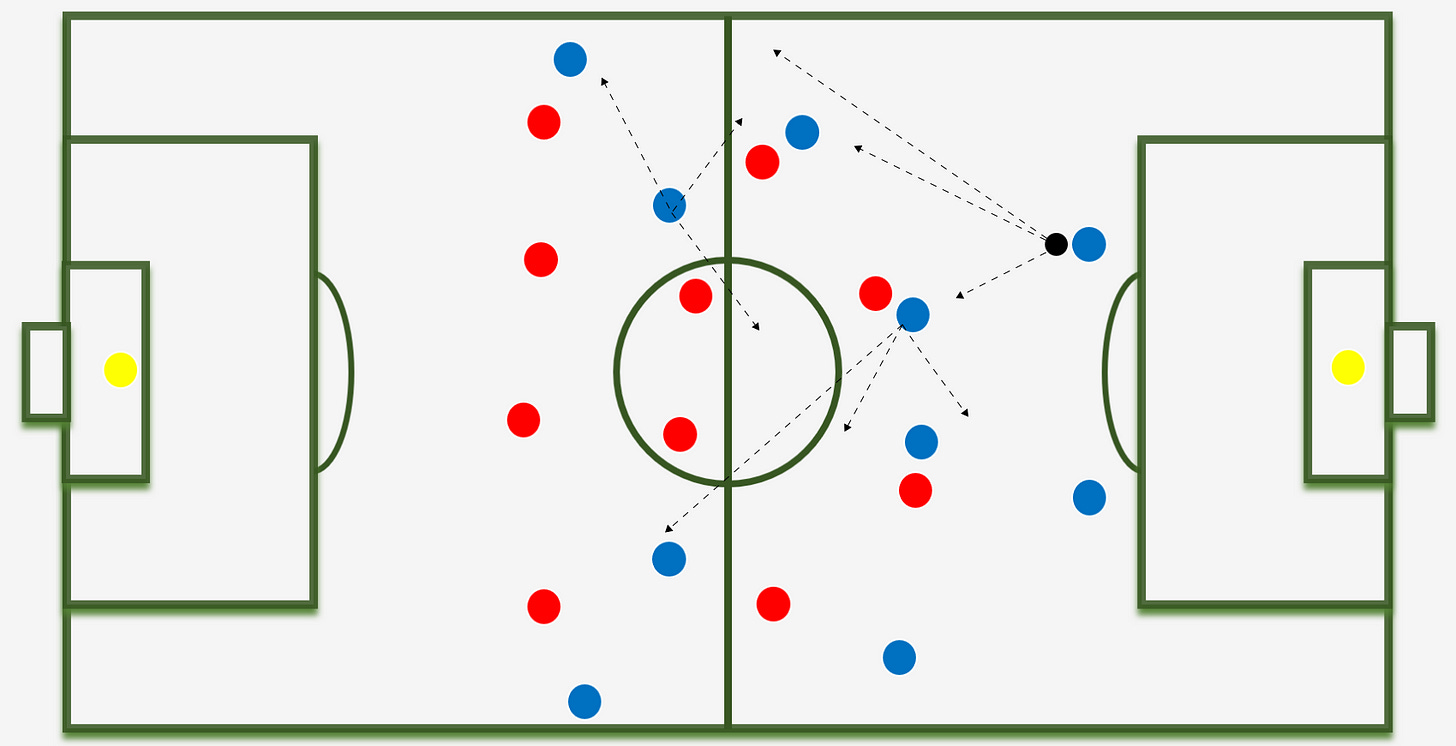

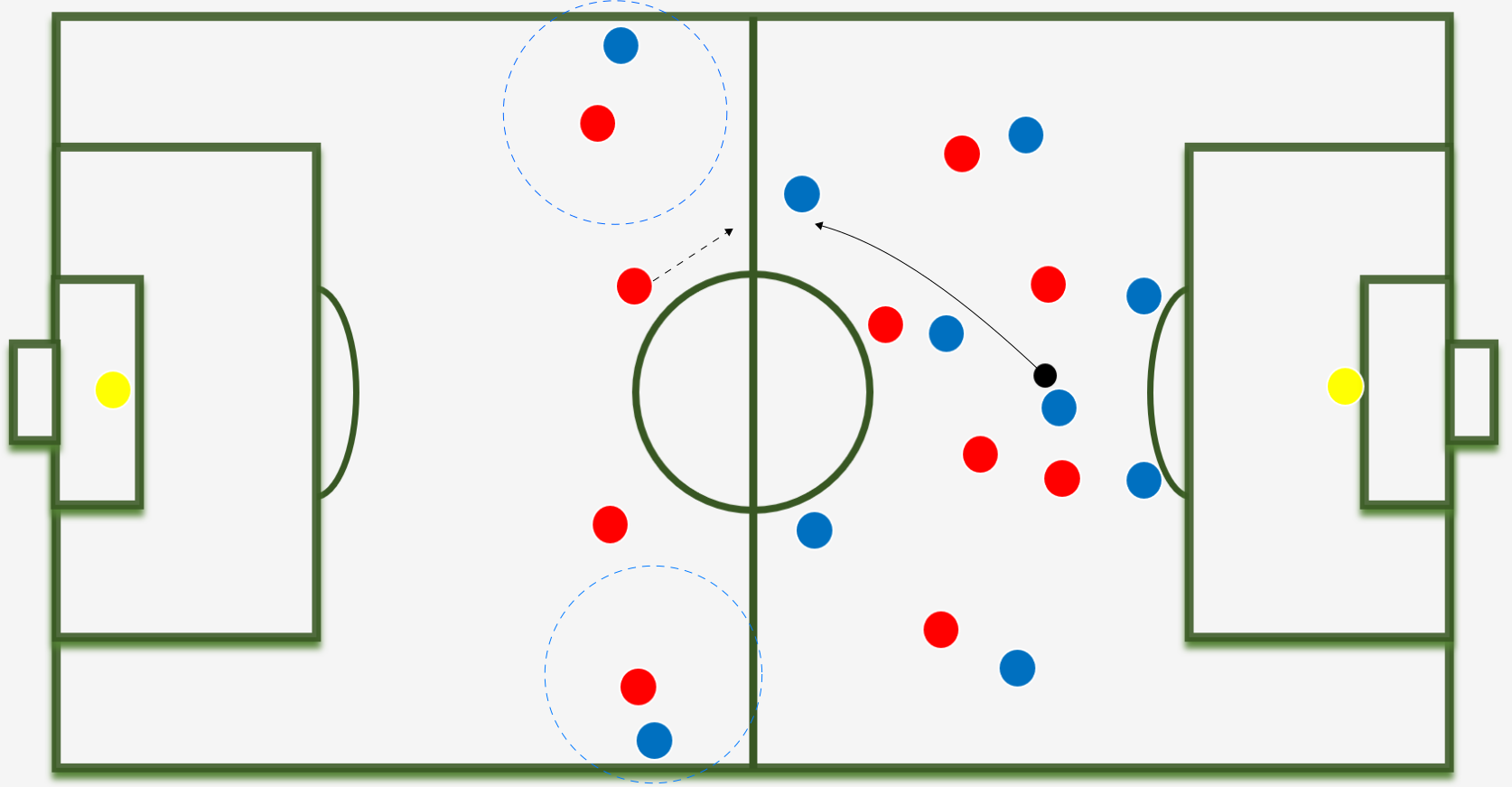

Passing is communicating. It tells the receiver of the possibilities of affordance. To clarify, here are some situations in which Brighton’s players often find themselves.

Assuming the players are acquainted with the circuits of play and aware of the possibilities within the build-up structure, the non-verbal communication through passing becomes much more concise and less vague for the players to interpret.

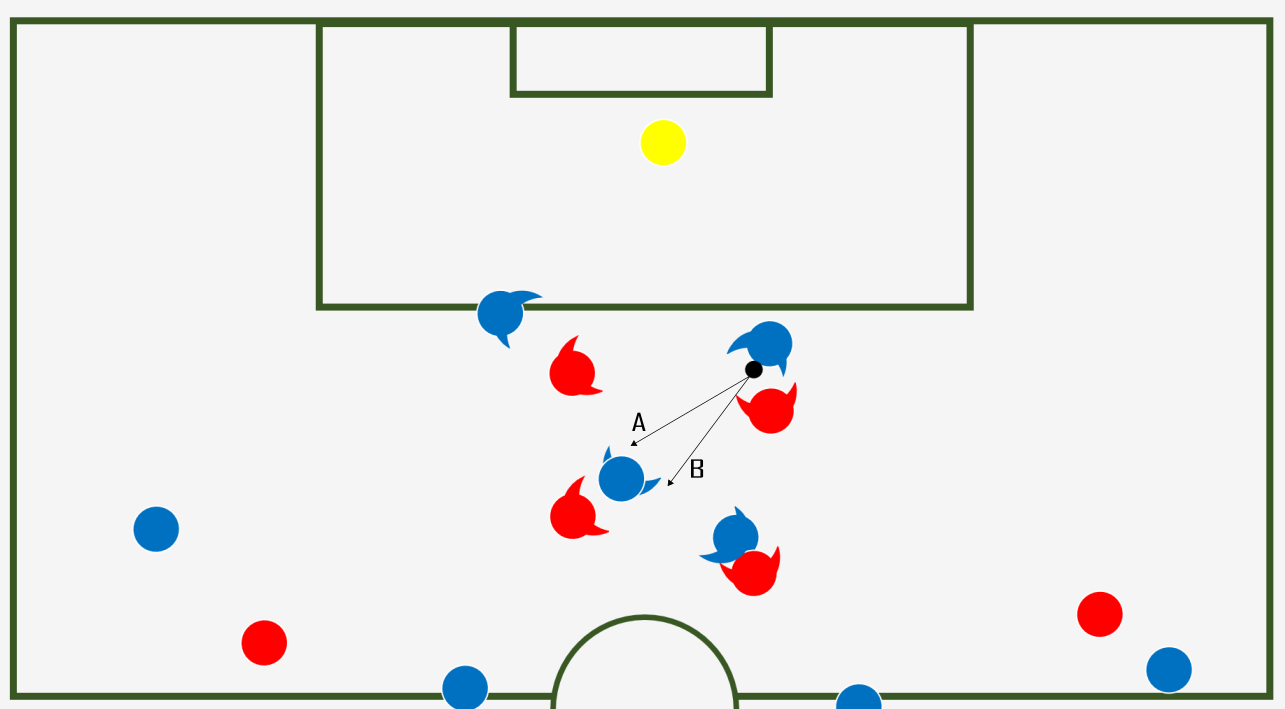

In the graphic above, A would suggest to the receiver that there is a possibility to first-time the pass to the other midfielder. B tells them that the pressure in their back is dangerous and that a bounce pass is in order. In this scenario, the CB will have spotted the ball-side centre-forward ready to drop in the half-space, allowing a ball into their feet with the space opened by the midfield bounce pass.

The B option would disincentivize a first-time lateral pass, as the body orientation of the first midfielder receiving would not protect the ball from pressure, while also taking longer to connect with the ball as the far foot is further from the ball than the near foot. Changing the body orientation from closed with your back to presser to open with your back to the sidelines would also disrupt the momentum of the body, destabilizing it and decreasing the power and accuracy of the pass.

Next to the direction of the pass, the weight of the pass also communicates the interpretation of possibilities by the passer. Together with the principle of direction, it is conditioned on the concept of vision. The centre-backs on the ball, facing the field, have more knowledge of the factors that should influence the next play. By all means, the midfielders with their backs to goal have to be knowledgeable of the factors behind them too. A few tools to make sure they do, and Brighton uses them well.

They all contribute to the concept of interpretative play.

Interpretative play suggests that through the perception of game-model-specific factors on the pitch – from teammate positioning to the pressing intent of the opposition – players interpret the solution most effective to the surroundings.

This can simply happen through the passer communicating to the receiver immediately as the ball starts to travel, a form of verbal communication common through all levels of football. But Brighton’s players excel at scanning too – the skill of perceiving the pitch by “scanning” for information.

Players can perceive the surroundings correctly without scanning too, however. When the coaches and analysts accurately describe the opposition’s shape, and behaviour, and accentuate spaces to play through, players have the capability to remember these cues, and use them on match day. This is not only a pre-match to match process, but it can also change during matches. Smart players, like Moisés Caicedo, can interpret game cues (pressing intent, direction, open spaces) in the first minutes of games, and adapt their decision-making on that basis, even without scanning before every action.

III.4 Baiting fish

The spiritual home of fish and chips, Brighton’s shores were industried by fishing for over one thousand years. Despite its decline in economical prominence on the south coast of Britain, Roberto De Zerbi’s team have continued Brighton’s rich history of fishing and baiting.

It is perhaps the concept most unique to the Italian’s game model – the short vertical spacing between the first two units is essentially just that: fishing.

The purpose of that spacing and timing is to bait a press, which creates space in the other half of the pitch to attack. In order to lure the opposition, they don’t use a literal fishhook, but they have a few tools up their sleeves to perform the football equivalent.

Individual-level: The studs

Setting the sole or studs on the ball is an individual tactic, and a popular one in De Zerbi-fans’ circles.

It is the closest analogy to the “fishhook” in the entire build-up. The centre-back (the fisherman) puts his studs (the hook) on the ball (the bait) and waits for the opposition forward (the fish) to engage the press.

This press engagement, in turn, is a trigger for Brighton’s group (two centre-backs and two midfielders) to initiate a pattern of play. In those patterns, the first pass is usually either to the diagonally-positioned midfielder, or a pass to the other centre-back.

The latter option, reveals another individual tactic that leans into the group tactics of Brighton’s build-up.

Individual-level: Staggering the first line

In build-up, the centre-back out of possession must stagger the horizontal line with his other centre-back in possession to create the angle to receive the ball. This “negative” pass entices pressure further, while allowing the receiving centre-back to control the ball and perform the next pass in time.

Group-level: Midfield movement

Another “bait” in Brighton’s game model is the movement of midfielders towards the ball when it is at their centre-backs’ feet. The trigger for this compressing movement is when the opposition decides to engage in their press.

Through compressing the pitch, further pressure is enticed. While the opposition’s first line of pressure is already closing down, the second line must also engage in the press, which opens “weak” space between the defensive and midfield lines. In those pockets, Brighton can receive the ball to feet.

In order to effectively receive the first pass (from centre-back to compressing midfielder), a few technical principles must be followed. First of all, the midfielder has to make a short-burst “pre-action” to dismark themself from the opponent, and then slow down to receive the ball.

With a view to exploit the “weak space” created by the press-baiting midfield movement, the receiving midfielder also should have support from a third man, or even the centre-back in some cases. That player can then play the ball into the weak space.

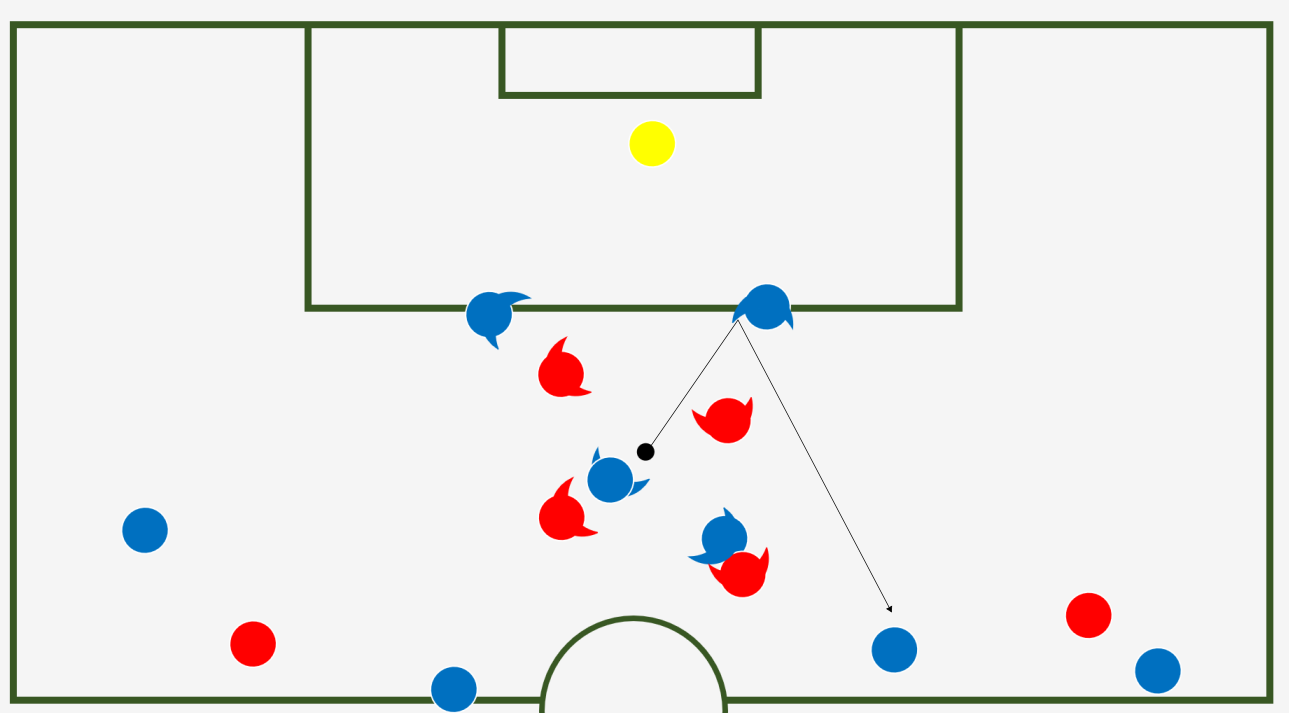

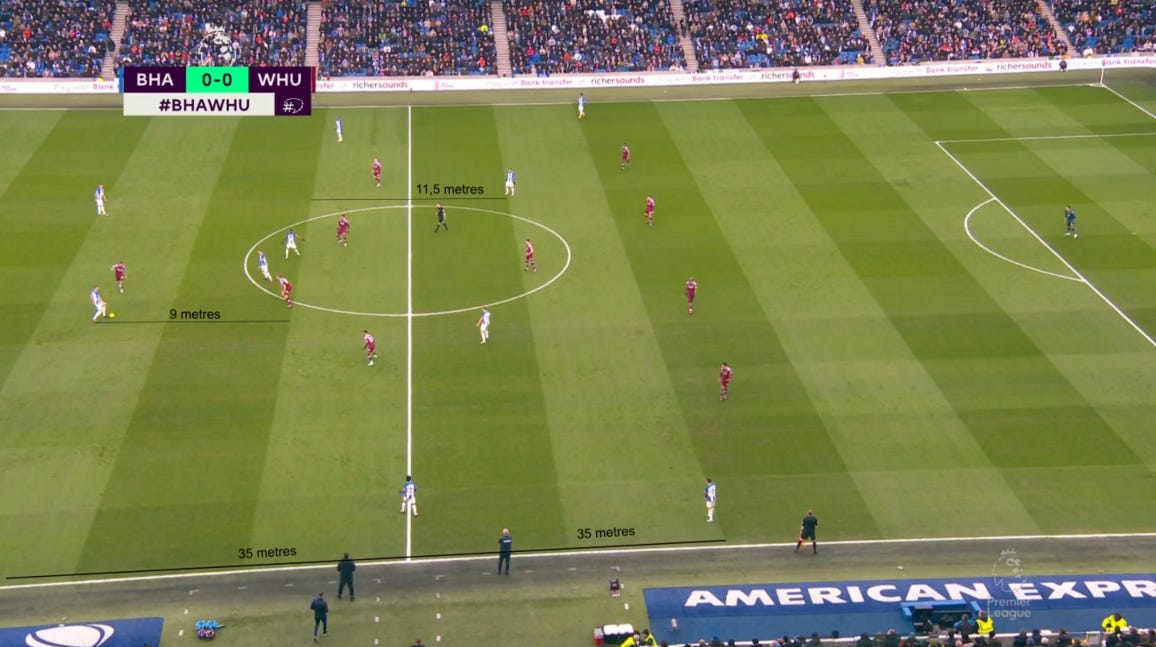

Team-level: Vertical spacing of groups

The full team-tactical extension of this group behaviour typifies De Zerbi’s main principles in the offensive phase. It is the spacing or distances between the groups of the team that build further on the abovementioned midfield movements, and allow Brighton to fully exploit their press-luring habits.

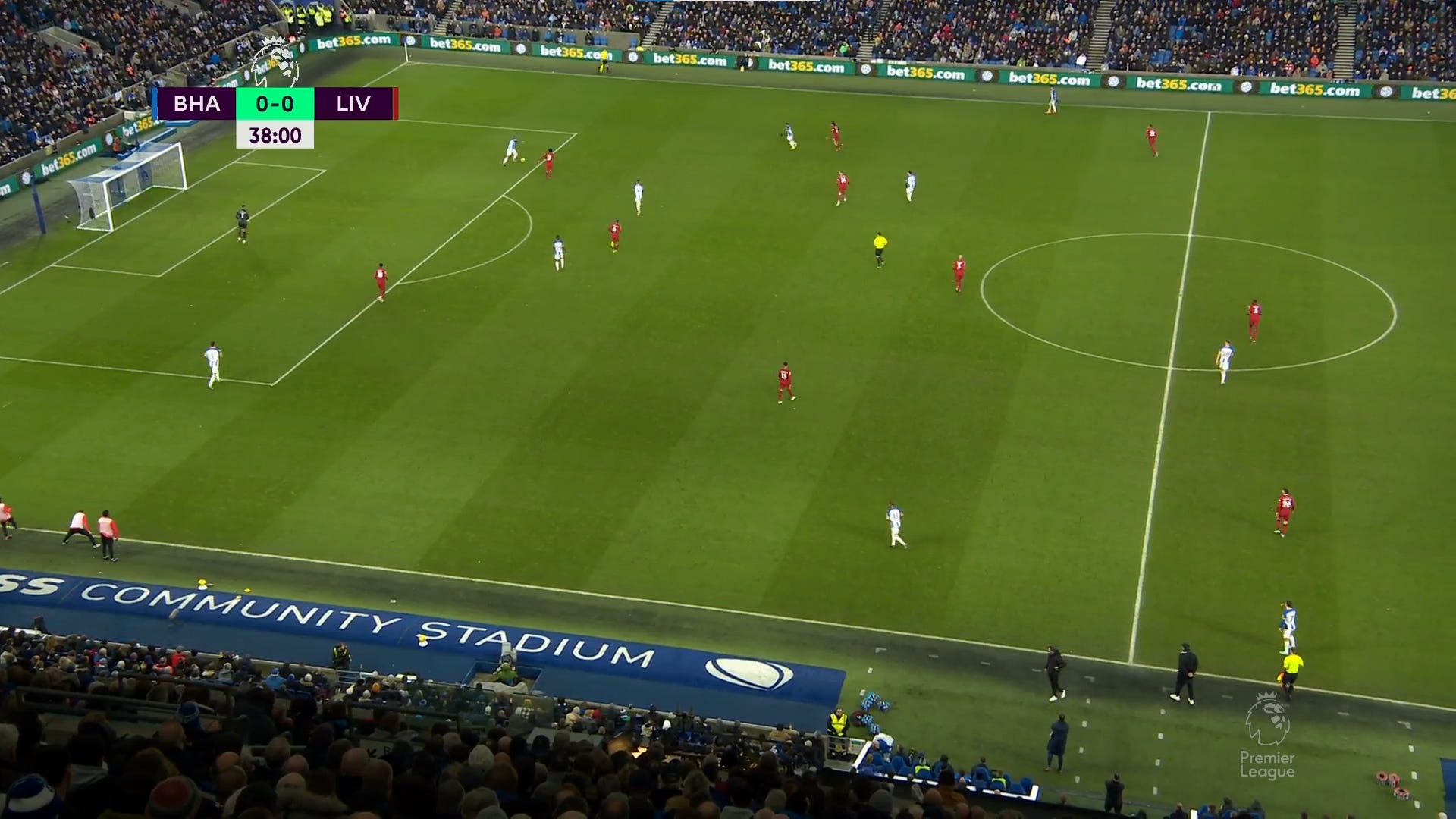

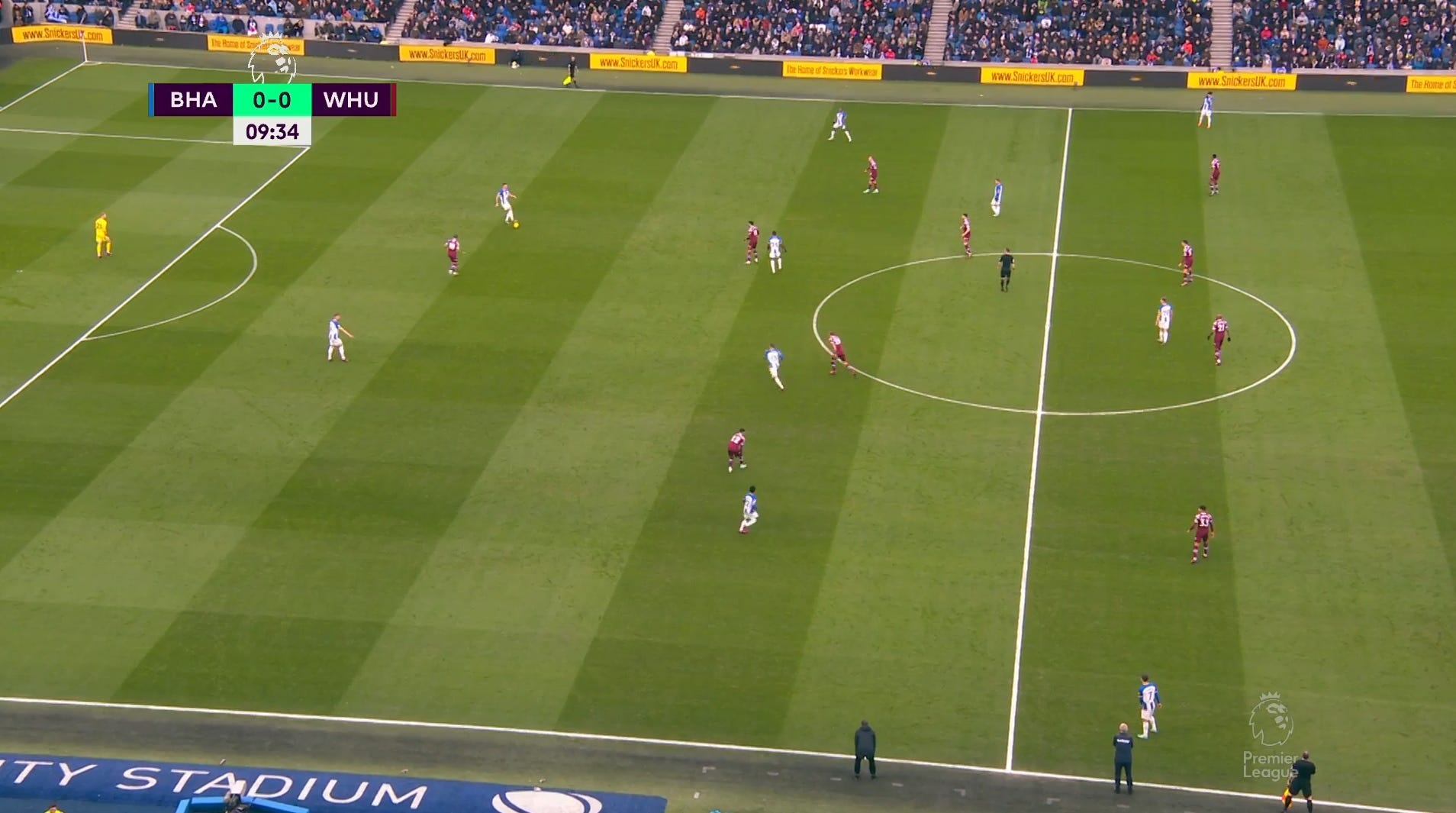

The close vertical spacing between the defensive and midfield line, entices pressure and creates a “weak zone” behind the opposition midfield line. Notice the particular occupation of Brighton players all around the pitch. The midfield close to the centre-backs, narrow full-backs as a second option to play through, the wingers on maximal width to pin the full-backs into a flat back line, and the two strikers dropping in the half-spaces to create an angled pass option between the lines.

Through enticing pressure on the centreback—midfielder group, and pinning the opposition full-backs (preventing them from jumping in pressing), Brighton can attack in 4v4 situations more often, should they beat the press.

This is also something Brighton player Adam Lallana has mentioned. From my angle, the keywords there are: “4v4s, 3v3s” and “a big space”.

IV. Bending time to control tempo

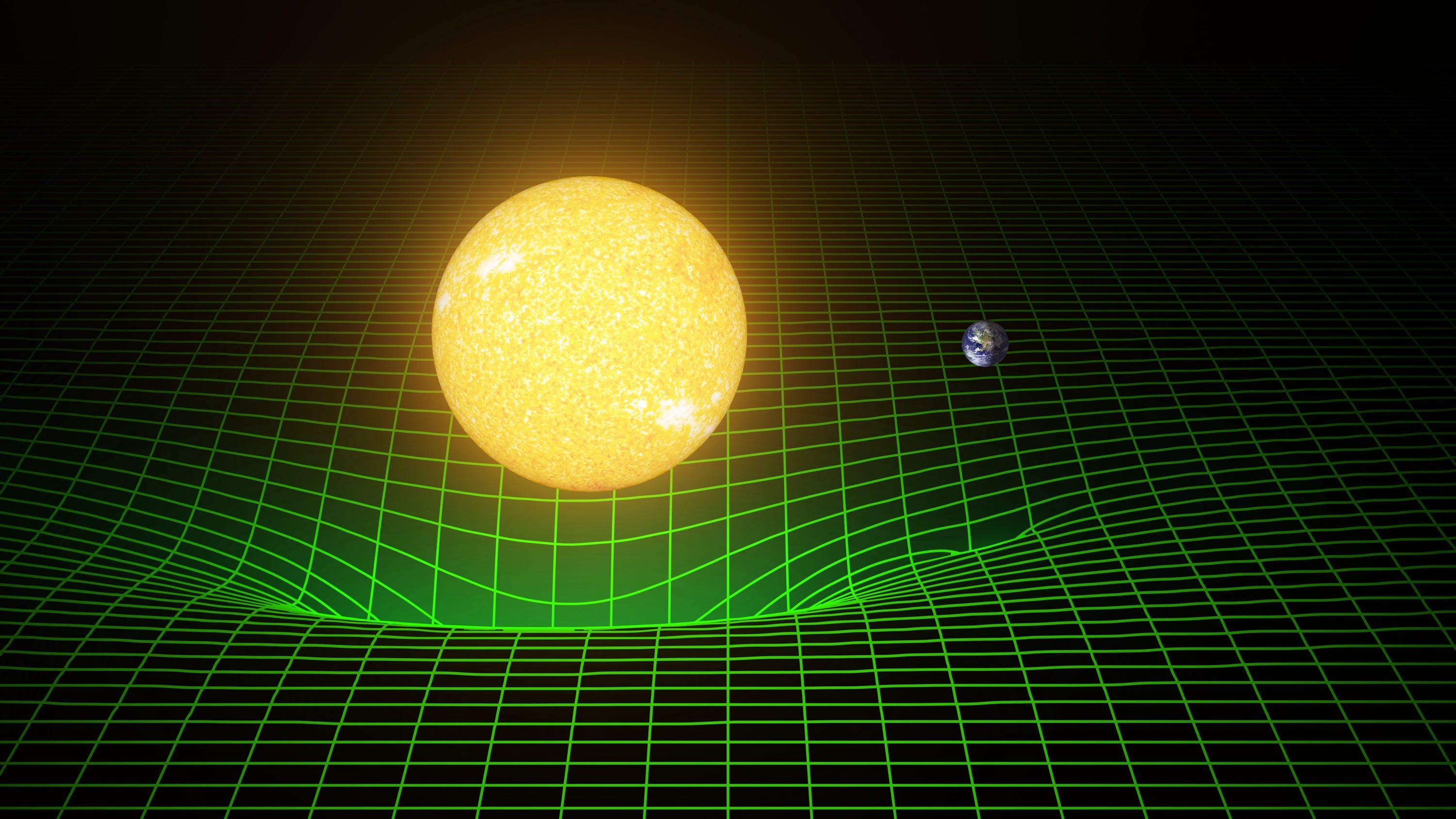

Albeit not to the extent of Albert Einstein’s fabric of space-time genius, Roberto De Zerbi’s build-up revolutionizes football spacing and timing as we know it.

The hourglass, at first glance a simple analogy to the structure of Brighton’s build-up play, also strikes an analogy with their respective contributions to time.

One measures time, the other manipulates it.

In order to control tempo in an effective manner, a team must first grasp “timing” on all layers. For Brighton & Hove Albion especially, the timing of actions is salient in their attacks (building, progressing and finishing it).

IV.1 Timing

Timing, in football, is everything. A pressing run can be successful or can fail solely on the timing of when the player decided to jump. A “pivot” receiving the ball from his centre-backs can lose the ball solely through bad timing of dismarking from their marker.

In any system, whether you imagine Sean Dyche’s Burnley’s long balls, Josep Guardiola’s Barcelona of 2009 or Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton & Hove Albion, timing is a crucial aspect of any action of any footballer.

As previously established, the possessional principles in Brighton’s build-up sub-structures calculate themselves on the great timing of coordinated actions by the group.

An example is the timing of when the diagonally-placed midfielder must drop to receive the ball from the centre-back, or when the striker must open the angle to receive the pass from the centre-back.

But the timing of Brighton’s offensive play is only a foundation brick for the way they control tempo in a football game.

IV.2 Tempo

When building the attack, the hourglass dictates tempo in an innovative way. The first chamber of the hourglass, the centre-backs, start the attacks very slowly. It’s their decision whether and when we see the tempo switches of Brighton’s attacks.

Through the three phases of the attack (building, creating, finishing), the Seagulls usually start with the centre-backs or even the goalkeeper. This measure is so radical, that re-organizing the attack is an over-arching pattern of play in Brighton’s model.

At the centre-backs’ feet, the attack starts at a low tempo – their job is to lure attackers in, by controlling the ball with the sole, playing negative passes, and carrying the ball up the pitch slowly.

Consider the centre-backs the Matadors of old, enticing the bull to engage, only to switch tempo and move dynamically on that cue. For Adam Webster and Lewis Dunk, our blue-and-white Matadors, their cue is the engagement of pressing by the forwards.

As soon as the press is engaged, the tempo drastically shifts from slow to fast, from 0 mph to 100 mph. This is a game cue for the entire team – the ball is now travelling beyond the first (two) line(s) of pressure, and a 4v4/3v3 situation is awaiting.

The tempo does not settle after this – Brighton’s dynamic wingers, skilled in 1v1 attacks, are relentless in locking on their target and exploiting the space.

It is Brighton’s unique press-luring individual, group and team-tactics that create the space and time for them to attack once they deem it right to do so.

On a macro level, the tempo management throughout 90 minutes is key to Brighton’s success too. By re-organizing play regularly, which allows players to restore their physical state, Brighton can dictate the intensity of a game. Since football is a complex athletic sport – short and long sprints, endurance runs and changes of direction – the way a team “restores” its physical condition is one of football’s most important aspects.

At the end of the article, it’s very late to shoehorn in some disclaimers, but alas.

This blog is not a complete analysis of Brighton & Hove Albion’s game model – it’s anything but that. It is a celebration of an (r)evolutionary team, which hyper-focuses on one aspect of their offensive play.

Secondly, the analogy of the hourglass is something that goes against my own personal view of football – I do not see football as fixed over-arching structures: it is not how I train players, nor how I believe it should be done. This article zooms in on the hourglass as one of the sub-structures Roberto De Zerbi’s side can use when building the attack.